Game Dev Story for the iOS (played on an iPhone 4.0) is one of the most addictive games I’ve played in years. This simulation game arms the player with a single secretary and $100,000 and asks them to – over the course of 20 years – build a videogame empire that creates the most successful game of all time. Unfortunately, when viewed as art instead of entertainment, its message conveys the depressing realities of the business end of the videogame industry.

Game Dev Story for the iOS (played on an iPhone 4.0) is one of the most addictive games I’ve played in years. This simulation game arms the player with a single secretary and $100,000 and asks them to – over the course of 20 years – build a videogame empire that creates the most successful game of all time. Unfortunately, when viewed as art instead of entertainment, its message conveys the depressing realities of the business end of the videogame industry.

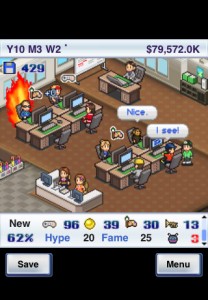

So let’s pretend the game isn’t art and talk about what the game does well. To create a game within Game Dev Story you must decide on a target platform, give your game a theme and a genre, and decide on an employee to take the lead when it comes time to create the scenario, character design, and music. Once your game is complete, you name it something silly, and put some marketing dollars toward increasing both corporate brand recognition. It doesn’t quite mimic what actually goes into real game development, but it does provide a fun, idealized version of it. It also offers a fun, nostalgic look at game history through its semi-realistic release schedule of trademark-friendly misnamed game consoles. I released games on the PC, Senga Exodus, Super IES, Game Kid, Sonny PlayStatus, Intendro DM, and the Intendro Whoops. The detailed pixel-art for everything from the game systems themselves, to the employees and how they catch on fire when they’re working hard is incredibly charming – charming enough to forget that you’re clearly playing a half-assed port of a pre-iPhone, non-touch cell phone game.

What makes Game Dev Story fun is the same thing that makes other simulation games like The Sims and SimCity fun. You’re injecting your own personality and decisions into a simulated world that exists with or without your input and witnessing the outcome. It nurtures our instinctual desire to leave our own mark on the world and try to make the biggest impact we can with our short lives. Using real history enhances this feeling, and it allows your own memories and game knowledge to fuel every decision you make. Why blow $10,000 on a licensing agreement to make games for the Virtual Boy when you know it’s going to be off the market in under a year? Why put all of your points toward cuteness when you’re making a War Simulation game? Why make a Puzzle game about the Stock Exchange when War Simulations are the more obvious sell?

What makes Game Dev Story fun is the same thing that makes other simulation games like The Sims and SimCity fun. You’re injecting your own personality and decisions into a simulated world that exists with or without your input and witnessing the outcome. It nurtures our instinctual desire to leave our own mark on the world and try to make the biggest impact we can with our short lives. Using real history enhances this feeling, and it allows your own memories and game knowledge to fuel every decision you make. Why blow $10,000 on a licensing agreement to make games for the Virtual Boy when you know it’s going to be off the market in under a year? Why put all of your points toward cuteness when you’re making a War Simulation game? Why make a Puzzle game about the Stock Exchange when War Simulations are the more obvious sell?

And therein lies the problem.

Because approximated history dictates your game’s sales there is very little room for innovation. Sure, when creating a game you can toss a few points in the innovation column, but a major factor in whether or not your game is successful is whether or not the theme and genre combination has proven successful. Make a Dungeon MMO and you’re in the money, but make a Dating Card Game or a Ninja Puzzle game and you’re shooting yourself in the foot. The natural instinct is to make safe decisions based on what you know sells instead of risking your fortunes on potentially strange combinations. To make matters worse, the game assigns a popularity letter grade to each genre and type, encouraging you to base your games on the more popular ones. Eventually you unlock the ability to make sequels, and creating one of these guarantees even higher sales.

I don’t blame the developers for structuring their game like this. They made the right choice. It’s entertaining and very rewarding, but as a window into human instinct it reveals a dark reality. When your fortunes rest on the success of a game, you’re more likely to structure that game around what you already know works. Why take chances when you can stick with what you know will be successful? Is it any wonder that the Activisions and EAs of the world have stuck with this model, only branching out via misguided PR attempts? When your motivation is strictly money you can’t afford to take chances. As you play the game you find all of your decisions will be based on this. In the beginning you may experiment with a few silly things, but as time goes by the game will mold you into this perfect corporate money grubber, stifling innovation every step of the way, firing any employee who under-performs, and outsourcing whenever you think it will benefit the bottom line. You have fun doing it, but the subtext is killer.

Over the span of 20 years I made 47 games. It’s telling that my only game in that entire period to win the Grand Prize at the Global Game Awards was a Motion Fitness sequel named Pandering DS2 for the Intendro Whoops (its predecessor was on the Intendro DM). I guess art imitates life, right?

-Wes